This case report aims to demonstrate the decision-making and planning involved in treating a case of midline diastema and how an interdisciplinary approach contributes significantly to achieving optimal results for the patient.

Aesthetic Dentistry is no longer a luxury. In today’s age of social media, everyone desires a beautiful smile, as it influences confidence and thus impacts one’s prospects for success in any field. From a dental perspective, achieving this requires a thorough assessment of dynamic facial soft tissues, skeletal structure, teeth, and their relationship with the lips and gingiva. Numerous parameters contribute to an aesthetic smile, including the facial and dental midline, gingival zenith, tooth size, golden proportions such as tooth-to-tooth proportion and tooth height-to-width ratio, tooth position, tooth shape, incisal embrasures, papilla height, contact areas, axial inclinations, and the shade of the maxillary teeth. The treatment plan we propose also depends on patient factors like time, budget, and the patient's motivation and expectations.

A diastema is a space between adjacent teeth with no contact between them. A midline diastema may detract from the aesthetics of a smile, as the dark space creates a visual gap. Possible causes of a midline diastema may include a wide dental arch, disproportionate tooth size or shape, a congenitally missing tooth, previously extracted mesiodens, or an active or hypertrophic gingival frenum. It is essential to differentiate a diastema from pathological tooth migration due to poor periodontal health. Factors like parafunctional habits, occlusal trauma, mouth breathing, tongue thrusting, and thumb sucking also need to be considered.

A 28-year-old male patient presented at the dental practice with concerns about gaps between his upper and lower anterior teeth.

Clinical Examination:

The midline diastema measured 2mm, with smaller diastemata present between central and lateral incisors and canines. The patient exhibited increased proclination in both the maxillary and mandibular arches and had a habit of tongue thrusting during swallowing. Periodontal health was good, with probing depths not exceeding 2mm, and periapical radiographs showed adequate bone levels. The temporomandibular joints were normal, with no history of dysfunction. A fleshy frenum was present in the midline, and the maxillary incisors were slender in shape, with inadequate height-to-width ratios.

Fig 1: Pre op in occlusion

Fig 2: Pre op in occlusion

Fig 3: Pre op in occlusion

Fig 4: Pre-op Maxillary Arch

Analysis of the diagnostic models showed that the spaces in the anterior teeth exceeded the amount of orthodontic retraction required in the upper arch. For the lower arch, the spaces could be managed solely with orthodontics. Prior to orthodontic treatment, the patient would need a habit-breaking appliance to prevent recurrence. Finally, the shapes of the teeth would need to be modified restoratively with lithium disilicate veneers or direct composites.

After thoroughly considering the patient’s aesthetic concerns, time constraints, and budget, we developed the following treatment plan:

1. Habit-breaking appliance

2. Orthodontics

3. Composite build-ups on teeth 12, 11, 21, and 22 (a decision regarding 13 and 23 to be made after orthodontics is completed)

4. Clear retainers

Phase One

A habit-breaking appliance was provided for 8 months. By the end of this period, the patient no longer exhibited tongue thrusting during swallowing.

Phase Two

Orthodontic brackets were applied to correct the proclination and close the spaces. The wire sequence used was 0.016 NiTi wire, 0.016x 0.022 NiTi wire, 0.016x 0.022 SS wire, and E-chain for space closure. This phase took 13 months. The spaces in the mandibular anterior teeth were completely closed with orthodontics. In the maxillary teeth, proclination was corrected, and the spaces were reduced and equalised between the four incisors to be restored with composite resin in the next treatment phase.

Fig 6: Post-orthodontic treatment completion

Fig 7: Maxillary incisors brackets debonded

Fig 8: Maxillary incisors brackets debonded

Fig 9: Maxillary incisors brackets debonded

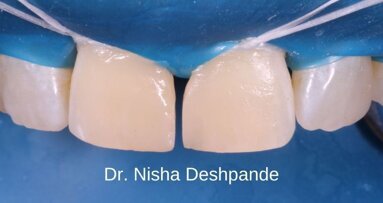

Phase Three

After the orthodontic treatment was completed, the restorative phase commenced. The orthodontist removed the brackets from the maxillary incisors, and impressions were taken and sent to the laboratory for a wax-up. A putty index of the palatal surface of the wax-up for the maxillary incisors was created to assist in achieving perfect symmetry. During the first appointment of this phase, the primary objective was to establish proximal contacts. Shade selection was performed using Vita Classic shade tabs and the composite button technique. Given the small spaces, a simple layering approach was chosen: an A2 medium translucency shade for the cervical area and an A1 medium translucency shade for the incisal area were selected. The teeth were isolated with a split dam, roughened using a coarse disc to remove aprismatic enamel, etched with 37% phosphoric acid for 20 seconds, and bonded using a 5th-generation bonding agent.

Fig 10: Putty Index of Wax-up

Fig 13: Composite buttons

Fig 14: Palatal Shell layering using putty index

Palatal shells were made using the putty index. Metal sectional matrices were positioned vertically with a wedge to establish the contact area. The final layer of composite resin was applied and cured under glycerine to eliminate the oxygen-inhibited layer. Gross finishing and an occlusion check were performed, and the patient was then referred back to the orthodontist for debonding of the lower anterior brackets. Once the lower brackets were removed, there was room to increase the length of the upper incisors to achieve the ideal golden proportions (where the widths of the central incisors should be approximately 80% of their lengths). An incisal edge build-up was completed, and line angles were marked on the composite to create perfectly shaped central incisors. Finishing was carried out with a focus on interference-free anterior guidance. Finally, the restorations were polished, and the patient was once again referred to the orthodontist for debonding of the remaining brackets and the next phase of treatment.

Fig 15: Matricing and Wedging

Fig 16: Polymerisation of Oxygen Inhibited Layer under Glycerine

Fig 17: Gross finishing done

Fig 18: Incisal edge build-up

Phase Four

The patient is continuing to use clear retainers following the completion of the composite restorations. Given the patient’s previous tongue-thrusting habit, the retention phase is expected to be extended. Currently, the restorations and occlusion remain stable. The patient has also been advised to undergo a frenectomy to address the slight black triangle in the midline, although this does not concern him. He is very pleased with the outcome after nearly four years of treatment. The patient has been instructed to avoid shearing with the incisor teeth and to visit the dental practice every six months for polishing of the composites.

Golden proportions are key determinants of an aesthetic smile. This case report presents an interdisciplinary approach to addressing aesthetic concerns such as diastemata caused by a combination of tongue thrusting and discrepancies between arch size and tooth shape. A combination of orthodontic and restorative treatment, underpinned by careful diagnosis and planning, was essential for achieving improved functional and aesthetic outcomes.

Some of the photographs have been tilt-corrected and cropped. No other digital editing has been applied to any of the photographs.

I would like to thank Dr Indranil Majumdar and Dr Komal Majumdar for entrusting me with this case. I would also like to thank Dr Aniket Gandhi for the provision of the habit-breaking appliance and orthodontic treatment.

Editorial note:

Suggested reading:

1. Claman L, Alfaro MA, Mercado A. An interdisciplinary approach for improved esthetic results in the anterior maxilla. J Prosthet Dent 2003; 89: 1-5.

2. Oquendo A, Brea L, David S. Diastema: correction of excessive spaces in the esthetic zone. Dent Clin North Am 2011; 55: 265-81.

3. Beasley WK, Maskeroni AJ, Moon MG et al. The orthodontic and restorative treatment of a large diastema: a case report. GenDent 2004; 52: 37-41.

4. Chu CH, Zhang CF, Jin LJ. Treating a maxillary midline diastema in adult patients: a general dentist’s perspective. J Am Dent Assoc 2011; 142: 1258-1264.

5. Goldstein RE. Esthetics in dentistry: principles, communication, treatment methods. Ed. B.C. Decker, 1998.

6. Gürel G, Bichacho N. Permanent diagnostic provisional restorations for predictable results when redesigning smiles. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent 2006; 18(5): 281-6.

7. Diedrich P. Preprosthetic orthodontics. J Orofac Orthop. 1996; 57: 102-116.

8. Cohen BD. The use of orthodontics before fixed prosthodontics in restorative dentistry. Compendium 1995; 16: 110-114.

9. Kalia S, Melsen B. Interdisciplinary approaches to adult orthodontic care. Journal of Orthodontics. 2001; 28: 191-196.

10. Rufenacht CR. Fundamentals of esthetics. Chicago: Quintessence; 1990.

11. Spear FM, Kokich VG, Mathews DP. Interdisciplinary management of anterior dental esthetics. JADA, Vol. 137 February 2006.

12. Woelful JB. Dental anatomy: its relevance to dentistry. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1990.

Topics:

Tags:

Vanini described an anatomical stratification technique that goes beyond the typical three dimensions (hue, chroma, value) of color. The technique, ...

The European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) chose “perio-ortho synergy”—a combined periodontal and orthodontic treatment approach—as the topic ...

Achieving a successful outcome in aesthetic dentistry can be a formidable challenge for all dental practitioners, regardless of their experience level. The ...

MOSCOW, Russia: Researchers from Austria, Germany and Russia have collaborated in successfully using lithography-based ceramic manufacturing (LCM), a form ...

In preparation for the upcoming Greater New York Dental Meeting (GNYDM) to be held from 25 to 30 November at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in New ...

In today’s era of digital dentistry – simulations and digital treatment planning can significantly improve the level of communication between the ...

Direct composite veneers are an excellent choice of treatment for aesthetic concerns. They are minimally invasive, have superior aesthetics, and are not as ...

The Blaster, although needs some modifications, can be a great addition to your armamentarium for restorative and adhesive dentistry.

This article is about a unique dental app called Denthue, where we interview its creator Dr. Sachin Chaware, Prosthodontist, Nashik. DentHue is a digital ...

Diastema Closure with direct composites is one of the most minimally invasive and often performed procedures in aesthetic and restorative dentistry. Yet, it...

Live webinar

Thu. 12 March 2026

9:30 pm IST (New Delhi)

Live webinar

Tue. 17 March 2026

5:30 pm IST (New Delhi)

Live webinar

Tue. 17 March 2026

10:30 pm IST (New Delhi)

Prof. Dr. Nadine Schlüter

Live webinar

Tue. 17 March 2026

10:30 pm IST (New Delhi)

Dr. Giuseppe Luongo MD, DDS, Dr. Fabrizia Luongo DMD, MS

Live webinar

Thu. 19 March 2026

4:30 am IST (New Delhi)

Live webinar

Thu. 19 March 2026

10:30 pm IST (New Delhi)

Live webinar

Fri. 20 March 2026

2:30 pm IST (New Delhi)

Mr. Andrew Terry Cert.DT. GradDipDH. Med, Cat Edney

Austria / Österreich

Austria / Österreich

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bosnia and Herzegovina / Босна и Херцеговина

Bulgaria / България

Bulgaria / България

Croatia / Hrvatska

Croatia / Hrvatska

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

Czech Republic & Slovakia / Česká republika & Slovensko

France / France

France / France

Germany / Deutschland

Germany / Deutschland

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Greece / ΕΛΛΑΔΑ

Hungary / Hungary

Hungary / Hungary

Italy / Italia

Italy / Italia

Netherlands / Nederland

Netherlands / Nederland

Nordic / Nordic

Nordic / Nordic

Poland / Polska

Poland / Polska

Portugal / Portugal

Portugal / Portugal

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Romania & Moldova / România & Moldova

Slovenia / Slovenija

Slovenia / Slovenija

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Serbia & Montenegro / Србија и Црна Гора

Spain / España

Spain / España

Switzerland / Schweiz

Switzerland / Schweiz

Turkey / Türkiye

Turkey / Türkiye

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

UK & Ireland / UK & Ireland

International / International

International / International

Brazil / Brasil

Brazil / Brasil

Canada / Canada

Canada / Canada

Latin America / Latinoamérica

Latin America / Latinoamérica

USA / USA

USA / USA

China / 中国

China / 中国

Pakistan / Pākistān

Pakistan / Pākistān

Vietnam / Việt Nam

Vietnam / Việt Nam

ASEAN / ASEAN

ASEAN / ASEAN

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Israel / מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Algeria, Morocco & Tunisia / الجزائر والمغرب وتونس

Middle East / Middle East

Middle East / Middle East

To post a reply please login or register